When we were bicycling around Bull Run Regional Park today, we found a plot of ground, bordered by a wooden split rail fence, with a sign identifying it as the "Harris Cemetery." Not knowing what it was, Kathy whipped out her trusty Google device and searched --

-- finding a web page of the Fairfax County Park Authority titled, "A Little-known African American Community at Bull Run" which reads in full as follows:

“… I have for some time past been convinced that to retain them in Slavery is contrary to the true principles of Religion & justice, & that therefore it was my duty to manumit them…”.

So wrote Robert Carter III in his Deed of Gift on August 1, 1791. Carter, one of Virginia’s wealthiest landowners, arranged to manumit the 452 people enslaved on his twelve farms, including the 809-acre Leo farm that spanned Fairfax, Loudoun and Prince William counties. Some of the 43 women, men and children emancipated from Leo farm would establish a small community in Fairfax County south of Centreville between Bull Run and Cub Run. Over the next 200 years their settlement would thrive, becoming one of the largest African American communities in Fairfax County.

Nathaniel Harris, Uriah Amager and their 18 family members settled north of Bull Run before 1810. By 1820, 12 households including the Harrises, Burkes, Paynes, Amagers and Clarks also established farms in the area and the population had grown to 52. Jesse Harris purchased the 211-acre “Waterside” tract in 1844. By 1859, the Harris family alone owned over 570 acres. As early as 1854, local families founded the Cub Run Primitive Baptist Church, which still stands on Compton Road. Throughout the next decades, all families were engaged in agriculture, producing primarily wheat and corn, and supporting local merchant mills and stores. Many were related to James Robinson, a free African American whose farm site is now preserved at Manassas National Battlefield Park.

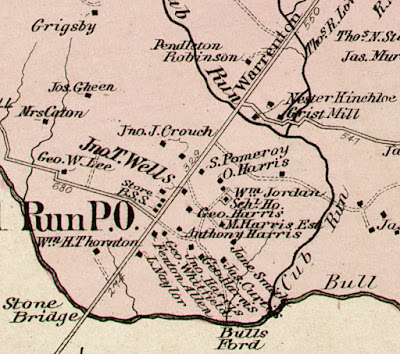

The free African American farmers above Bull Run were not spared when the Centreville region became a battleground during 1861-1862. Confederate and Union Armies repeatedly destroyed property and requisitioned crops and animals. After the war, Jesse and Obed Harris filed claims with the Federal government. Each received compensation for property that Union forces had taken in 1862. Families resumed life and slowly regained economic footing. In February 1868, Charles Harris successfully appealed to the Freedmen’s Bureau for $150 to complete a school for local children. The Rock Hill “Schl Ho” sits among the Harris, Naylor, Jordan and other homesteads that comprised the community in 1879, as seen on G. M. Hopkins’ map of Centreville District No. 1, Fairfax County (detail, Library of Congress).

Historical cemeteries and the Cub Run Primitive Baptist Church are among the few known physical remnants of the African American community that once flourished at Bull Run. Nonetheless, many proud descendants of families who established and once resided there enthusiastically research and share information that sheds light on their ancestors.

Author Heather Hembrey is the Assistant Collections Manager for the Archaeology and Collections Branch. Her research is used to inform the archaeological work done throughout the county.

-0-0-

It was fascinating to learn that free Black persons formed a community in the area, but it was doubly interesting to find, when we examined the map in the photo above, that virtually all of Bull Run Regional Park sits on land formerly owned by members of that community. All we had previously known about the park's history was that it saw quite a bit of action during the Civil War, most notably at Blackburn’s Ford, where a federal brigade attempted to cross, but Confederate fire forced Union commanders to cross the creek farther upstream. The site of Blackburn's Ford is visible just a short walk down the Occoquan Trail along the creek, near the crossing of modern day Route 28. In addition, the 19.6 mile Bull Run Occoquan Trail served over the years as part of a system of Native American trails, trade routes, and later as civil war supply routes.

Leaving our bicycles and walking into the cemetery, we found that an area within the fencing has been mowed from time to time, but is fairly rough ground. Rough unengraved stones mark some of the graves.

A closer examination of the sign at the front of the cemetery --

-- reveals that a certain Andrew LaFosse led a crew to clean up the cemetery (and possibly uncover and reset headstones) in 2009 and 2012, as part of a Scout project. We tried to find information about that project, but were unsuccessful, so poor Andrew's work will have to get only this much credit.

All of this is to show that you never know what interesting history you'll find when you turn the next corner!

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.